Frustration with elected officials has increasingly taken the form of a simple accusation: “They are not representing us.” Politicians are condemned for voting against opinion polls; party bases revolt when leaders compromise, and populist movements promise to return power directly to “the people.”

Beneath all this lies an unexamined assumption about what democratic representation is supposed to mean — namely, that representatives ought to function as delegates who transmit the immediate preferences of their constituents into law.

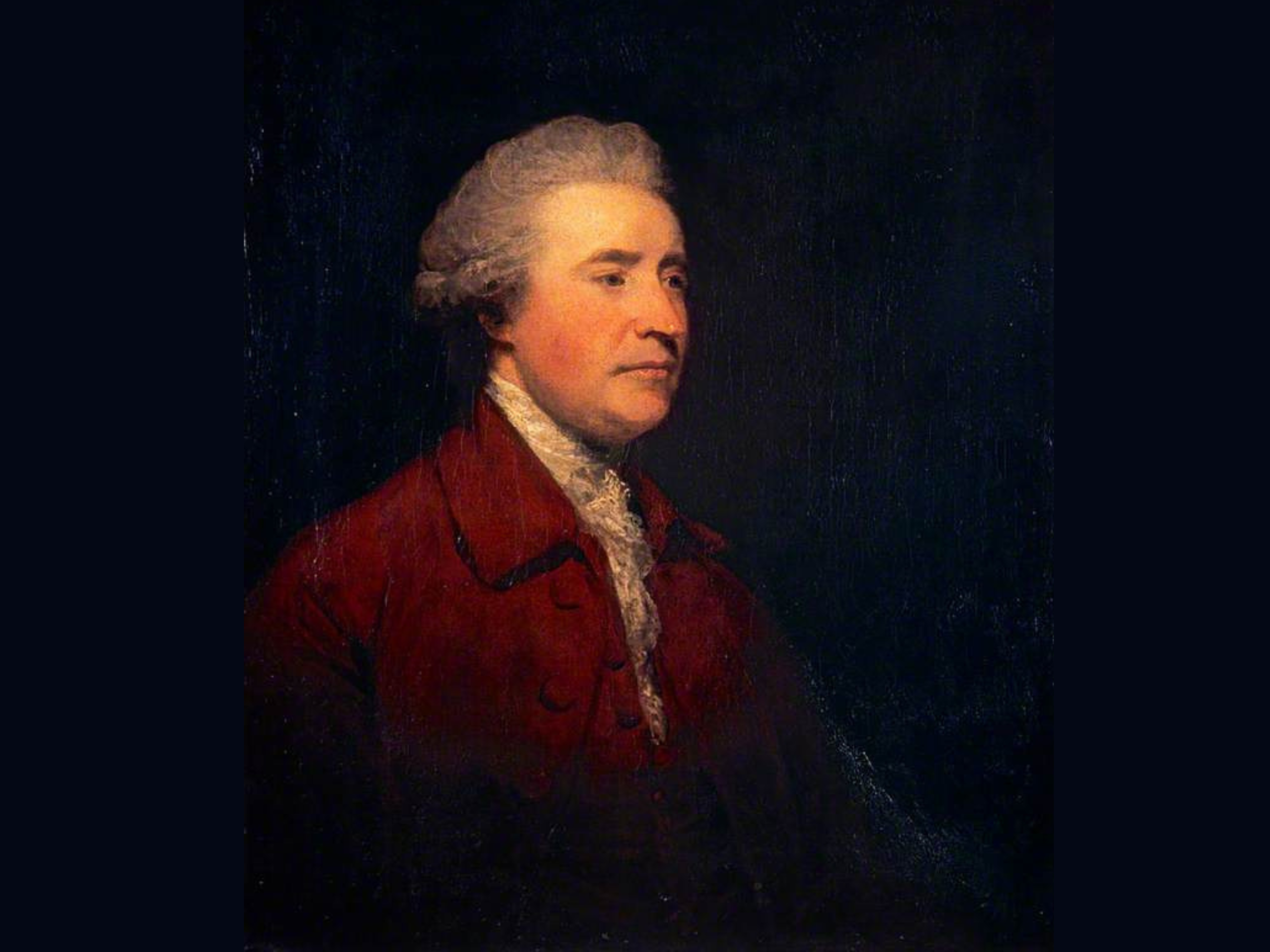

But that understanding of representation is far from the only one available. Edmund Burke, the 18th-century member of British Parliament, suggests nearly the opposite in his influential account of political representation. And — perhaps surprisingly — Catholic social teaching (CST) aligns more closely with Burke’s model than with today’s popular majoritarian instincts.

Broadly speaking, political theorists tend to distinguish between two main models of representation. The first is the delegate model, in which an elected official acts as a kind of messenger, carrying the expressed will of voters into legislative chambers. On this view, personal judgment is secondary; the representative’s duty is to reflect popular opinion as accurately as possible.

The second is the trustee model, most famously articulated by Burke in his 1774 speech to the electors of Bristol, later published as, “The Position of a Member of Parliament.” Burke insists that while representatives owe constituents their attention and concern, they do not owe them blind obedience. Parliament, he argues, is not a congress of “ambassadors” from competing local interests but a deliberative assembly oriented toward the good of the whole nation. A representative who sacrifices his own judgment to popular pressure “betrays instead of serving” his constituents.

For Burke, representation is not a mechanical transmission of preferences but a moral responsibility. Elected officials are entrusted with exercising prudence, reasoning about complex matters, and sometimes resisting the immediate passions of the public in service of the common good.

CST may seem distant from these debates in representational theory. Its documents do not speak in terms of trustees or delegates. Yet when one examines CST’s underlying assumptions about political authority, the common good and moral responsibility, a clear picture emerges that strongly resembles Burke’s trustee model.

Central to CST is the conviction that political life is ordered toward the common good, understood not simply as the sum of individual preferences but as the set of social conditions that allow persons and communities to flourish. Human dignity, natural law and objective moral limits all place boundaries on what rightly can be decided by majority vote. As St. John Paul II warned in “Centesimus Annus,” democracy detached from moral truth risks devolving into a thinly disguised form of totalitarianism.

This alone undermines the idea that representation consists merely in reflecting whatever the majority wants at a given moment. If some actions are unjust regardless of popularity, then representatives cannot be morally obliged to enact them simply because they are demanded.

Moreover, CST places heavy emphasis on virtues such as prudence and conscience in public life. Political leaders are repeatedly described as having the responsibility to discern, deliberate and act wisely. Their role is not passive but active — requiring judgment in the face of competing interests and complex realities.

This moral vision fits naturally with Burke’s insistence that representatives must exercise independent judgment. Both CST and Burke treat political office as a trust, not a mandate to obey fluctuating public opinion. Both see representation as a mediating practice that transforms diverse voices into reasoned law through deliberation.

The principle of subsidiarity, often reduced to a call for decentralization, presupposes this kind of prudential judgment by legislators tasked with weighing interests across different levels of society. Higher authorities are not meant to micromanage lower ones, but neither are they stripped of the duty to intervene when the common good is threatened. This requires discernment, not automatic responsiveness to popular pressure.

None of this implies contempt for voters or indifference to public concerns. Burke emphasized that representatives must listen carefully to constituents and take their interests seriously. CST likewise affirms participation and the importance of civic engagement. However, participation does not mean direct control over every political decision; it means contributing to a political order in which entrusted officials deliberate responsibly on behalf of all.

In an age shaped by social media outrage, instant polling and constant demands for ideological purity, the trustee model of representation can feel uncomfortable. It asks citizens to accept that their representatives may sometimes disagree with them — and that this disagreement is not necessarily a failure of democracy but a feature of it.

Yet this older understanding may be precisely what democratic governance requires if it is to remain stable and oriented toward genuine goods rather than momentary passions. Far from endorsing a populist vision of politics as the raw expression of popular will, CST points toward a richer and more demanding conception of representation, similar to what Burke articulated more than two centuries ago.

This peculiar convergence between Burke and CST reminds us that democracy is not merely about counting preferences but about cultivating the prudence that undergirds a humane political community.